Intro

Do you want me to slow him down, sir, or do you want to send in some more guys for him to beat up?

There’s a scene in The Winter Soldier that is so cool they reprise it in Endgame: Captain America (Steve Rogers) gets into a glass elevator followed by Brock Rumlow, and the elevator is loaded up with as many Hydra agents1 as you can fit in one elevator.

There is some dialogue between Brock and Steve, but it’s inconsequential. More important are the carefully averted stares and tense stances.

Then there is a magnificently choreographed fight. Steve is the star, no doubt. And Brock (later Crossbones) is the bad guy, but the scene is built around an elevator crowded with opponents. And though they might be called “stunt men” they are IMHO serious actors. They might not say much, but their physical acting is important to the scene. Still, we don’t know who they are2.

These unnamed characters are important to a movie, and there can be a long list: “Bigger than Ben Hur” isn’t a phrase because Ben was big. It was because of the epic and extravagant scope of the 1959 film – apparently it had over 10,000 extras. But the sheer number of such characters doesn’t really show how important they are – most of the extras in Ben Hur are just background.

I thought it might be interesting to investigate just how important these unnamed characters are to the Marvel Cinematic Universe (MCU). And I think the results tell us something pretty deep about our societal beliefs about the value of certain roles.

Superhero movies are driven by conflict

Let’s take a step back. Superhero movies are sub-genre of action movies3. The audience is there to see action, not drama, or monologues, or music although these aspects are important.

Action is driven by conflict: Man v World, Good v Evil, or Avenger v Avenger, it’s all grist.

So superhero movies are driven by conflict.

What can we do with that?

One thing that intrigues me is that much of the infrastructure for talking about parts or roles in movies is not based on action. Movies still pay tribute to their origins in the theatre, in the same way that we still use QWERTY keyboards long after the reason for this confusing layout has gone.

We see this in how Hollywood allocates credit. Actors’ parts are broken down largely by how much dialogue they speak. Major parts might be given precedence by other factors (the seniority or fame of the actors), but as a rule, major roles involve lots of speaking, and less important roles less. It is sometimes formalised, e.g., by actors’ trade unions, into categories such as

a bit part is one with no more than 5 lines; and

an extra (or background talent or atmosphere or supernumerary or junior artist) is a “silent” role4.

Bit parts might be listed in the credits. Extras are often omitted, but might be noted in sources such as IMDb where the actor was identifiable. But in an action movie, even the least extra character may play an important part without saying anything. They can be

killed to show how a power, or device, or monster works,

killed to show how evil a bad guy is,

killed (accidentally) by a good guy to create angst,

an acceptable target (to be taken down by an otherwise peace-loving hero); or

in some cases an “extra” may even be a serious obstacle.

And yet these characters generally remain unnamed5 and unloved. They might be seen as disposable, and unimportant, but if they are used badly, a film seems staged and artificial. When used well, they add to the action and pacing and sometimes the humour of a movie. So let’s have a closer look at these humble, unnamed characters.

Mooks

They may be called the Palace Guard, the City Guard, or the Patrol. Whatever the name, their purpose in any work of heroic fantasy is identical: it is, round about Chapter Three (or ten minutes into the film) to rush into the room, attack the hero one at a time, and be slaughtered. No one ever asks them if they wanted to.

I can’t keep calling them ‘unnamed characters’, so I’m going to call them mooks. You could call them minions or extras or small fry or drones or pawns or grunts or lackeys or cannon fodder or flunkies, but all of those terms are loaded with meaning, and as Lewis Carroll’s egg said, I want a word to mean what I choose it to mean. It’s easier to enforce that when the word isn’t too heavily invested with other meanings6. The simple definition of mook paraphrased in many places is “a stupid or incompetant person”, but that dates back to the 30s in the US and isn’t common anymore. I won’t be using that meaning.

I like the way the RPG Feng Shui uses the word:

A less powerful enemy, easily dealt with, often appearing in large groups to present some challenge.

This usage does seem to be seeping into descriptions of the superhero genre: e.g., some quick quotes:

The Winter Soldier pits Cap against a dozen SHIELD/HYDRA mooks with stun clubs

One mook (Eric Oram) does confess to Stark that, “Honestly, I hate working here. They are so weird.”

So let’s be precise here. My definition is

mook (noun) /mu:k/ A disposable character (or sometimes an object), often appearing in groups, usually unnamed (not given a proper name), included in some form of conflict to illustrate main characters’ abilities or intent or emotions, or just to increase the amount of action.

I am not using “mook” in a derogatory sense here. I am deliberately not saying “less powerful”. Some mooks are powerful in their own way, but this is usually limited or narrow. TV Tropes description is “Deadly, competent, loyal, abundant… pick any two.”

The point is, they aren’t always cut down like chaff (though we will see that they usually are).

And they don’t have to be “minions” in the sense they can be independent of a villain’s control. They can be part of their own organisation, or independent.

I also do not automatically assume mooks are bad guys. The role such characters play is often the same whether they are opposing heroes or villains. The Red Shirts of Star Trek are mooks by my definition. And sometimes mooks were coerced, or mind-controlled, or they can be converted to the cause. So good/evil distinctions aren’t a necessary starting point, but we’ll see that most mooks are effectively evil when we look at the data.

They don’t even have to be a person, as such. In many action movies, objects take on many of the roles of a human either through explicit anthropomorphism (Doctor Strange’s Cloak of Levitation), or indirectly as a Mcguffin or other plot device. And such objects can often have at least as much character and verve as any other extra. In conflict, often an air or space craft is an important adversary – the interaction is dominated by the characteristics of the craft involved – and we might not even see the pilot. So we can think of these as a type of object-mook.

The goal of this definition is not just to specify exactly what I mean, but also to make it possible to automate some of the process of analysis. I want to do a few simple things, like work out how often mooks play a role in a movie, and having a relatively broad definition is helpful. But I did have to do some work to collect the data, so I’ll describe that next, along with some results.

The data

If the topic is conflict, then we can’t simply dissect the dialogue of a movie as is commonly done in narrative analysis. Instead I watched the whole MCU again. That wasn’t too painful – I really like the movies (you may have guessed) – but I also annotated every conflict, and who was involved (a named character or mook). I could talk a lot about the annotation process, but you’d probably get bored, so I will perhaps leave that for another time.

One or two words are needed though. Here we define a named character as one who has a proper noun as their name, i.e., Tony Stark. Everyone else is unnamed, even “Tony Stark’s secretary,” but certainly “SHIELD agent” isn’t a name, it’s a designation. The unnamed characters form our pool of mooks, but only become relevant if they are involved in (non-trivial) conflict.

The classification into names characters is facilitated by a couple of big files (see https://github.com/mroughan/AlephZeroHeroesData/tree/master/MarvelCinematicUniverse) of character names, primarily built by hand using credit lists from IMDb, and various other source material.

A “conflict” is a rubbery concept. Roughly it is an indivisible set of actions between opposing characters, usually in the form of a physical fight. Here we try to break fight scenes down as much as possible, so conflicts are fairly short, but that can range from sub-second, to a few seconds. So a character’s contribution to the movie isn’t purely a function of the number of conflicts, but that’s what I can count.

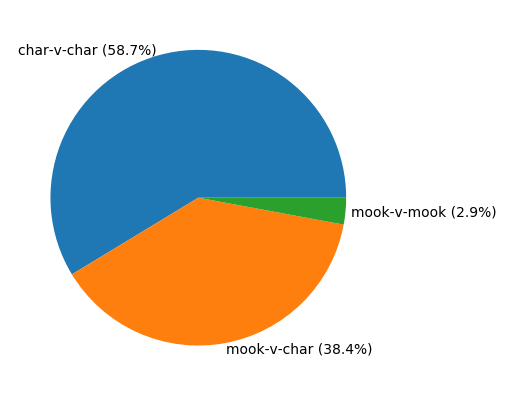

The overall picture is shown in the pie chart. Overall about 40% of conflicts involve mooks. That gives us grounds to say that mooks are a critical part of modern action/superhero movies. So let’s find out a bit more about these surprisingly important MCU mooks.

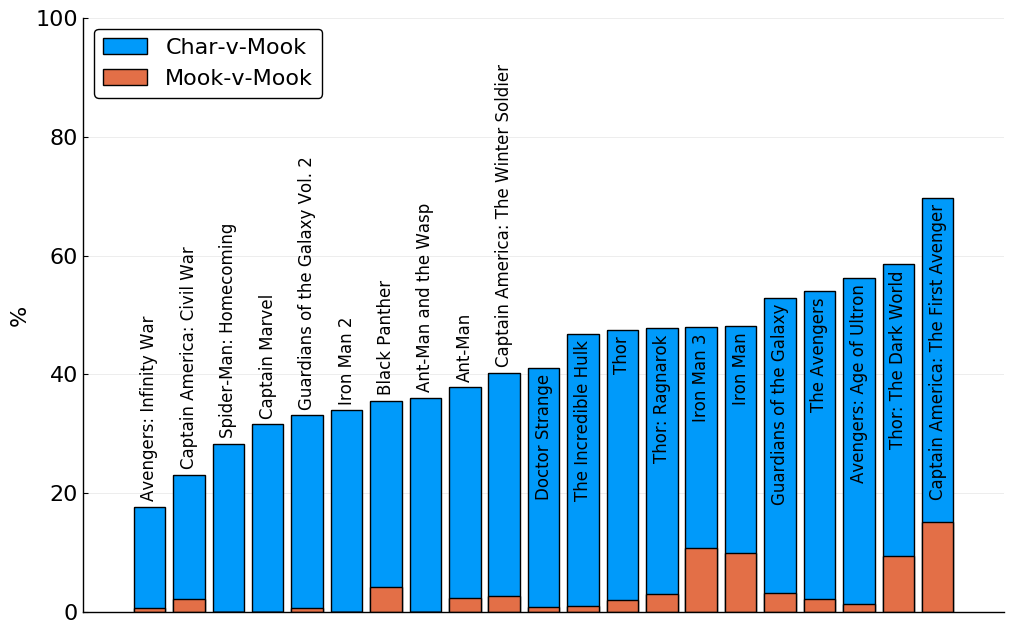

The following table (click on the table to see the data directly) lists mook participation by movie. It only covers the movies up to Captain Marvel because I haven’t had a chance to process End Game. The table lists the movies and the percentages of conflict by who was involved. The results are also illustrated in the bar chart below.

The really interesting feature of this data is how much variation there is. We have less than 18% of conflicts in Infinity War that involve mooks and Civil War is similar. Almost all of the action is the main characters. That isn’t surprising: both movies are team ups of large groups of well-known characters (in the main), and so (i) characters don’t have to establish their bona fides by beating up a bunch of no names, and (ii) there are plenty of opportunities for main characters to beat up other main characters.

On the other hand we have movies like Captain America where nearly 70% of conflicts involve mooks.

And we see everything in between these two extremes. We see a small cluster with total mook participation of 47-48% (from The Incredible Hulk to Iron Man), but otherwise there seem to be a continuous range of values.

What mook is that?

Most mooks belong to a group. Some are direct minions of a villain, but often they are only employees (mercenaries being a common example). Other times they are from a semi-independent organisation, which is bigger than any one villain (e.g., Hydra).

Going through the movies, I classified the mooks by the group they belonged to7. The groups are shown in part in the following table (click on the table to get a link to the full list). The table also shows the cumulative percentage so we can see that the top-10 mook groups account for nearly 50% of all mook participation.

I don’t think there are any big surprises there. Hydra is the secret (evil) organisation that provides the backdrop for many of the movies (opposed and interwoven with SHIELD), and supplies many of the henchmen and minions. Ultron has a hoard of robot minions, and the Chitauri are the bad guys in the epic “Battle for New York” in The Avengers. Soldiers and Guards, Police and Criminals also feature heavily. If you follow the link you will see many other types, most of which come from more specific groups of movies and who consequently appear less often.

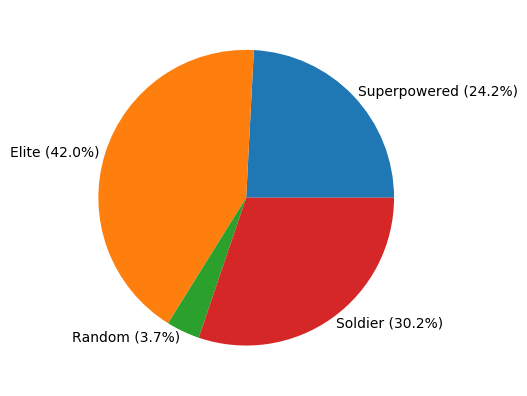

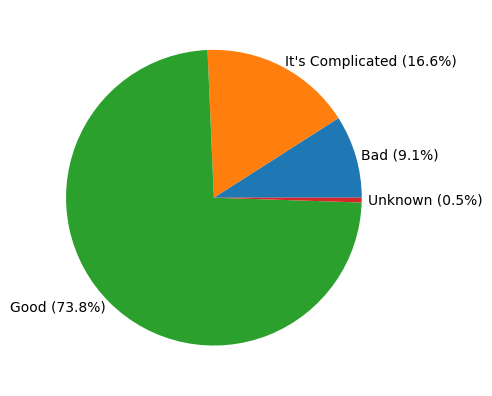

If we want to understand these groups, we need a coarser grouping, a version of which I have shown in the pie chart. Here I used this table to put mook groups into categories roughly according to their fighting prowess. The Random mooks are mostly civilians; the Soldiers include other armed and trained groups such as police; the Elites are elite soldiers (SHIELD and Hydra for instance); and the Super category includes mooks that are superpowered beings in their own right, for instance, the Extremis-fired mooks of Iron Man 3.

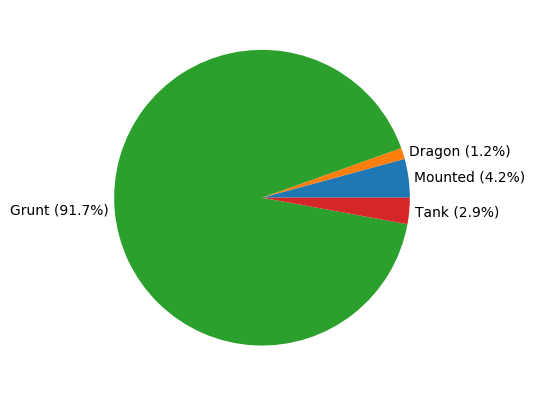

The other way to break the mooks down in terms of power, is to look at how they are used as individuals. My categorisation is:

Grunt mooks – these are your plain vanilla disposable mooks.

Tank mooks – these aren’t literal tanks. Drawing on terminology from computer games, they are the big-bruisers, a cut-above the average mook. Often a big guy, sometimes a guy wearing powered armour or the like. The feature that distinguishes a tank from the vanilla mooks is that they stand up and fight a superhero for more than an instant.

Mounted mooks – these are mooks who are riding an animal, or more commonly piloting an aircraft or spacecraft, usually armed and armoured, often flying but definitely more mobile than the average mook. Think of them as the cavalry.

Dragon mooks – these are really big, and really cranky; they are named such because sometimes they are a literal dragon, or dragon-like monster, but other times a big well-armed spaceship.

Unsurprisingly, the vast majority of mooks are “vanilla” mooks. Tanks, for instance, are only used as particular obstacles in a heroes narrative, and thus contribute only a small percentage of instances. Likewise Mounted and Dragon mooks, who play a similar role, and have a similar scarcity. The vast majority of mooks are, in fact, chaff.

Good v Evil(ish)

The movie is not about the mooks. It not called “Captain Mook” or “The Incredible Mook.” It’s about the heroes and villains. The mooks are supporting acts, so we expect that mooks will fight villains and heroes. Mostly that is true, as we saw above. With the exception of

- Captain America: The First Avenger

- Thor: The Dark World

- Iron Man

- Iron Man 3

the vast majority of mook conflicts are against named characters. And these movies all have large-scale battles involving mooks on both sides.

But what type of characters do the mooks fight? We could analyse them in a few ways, but the most interesting seems to be whether mooks primarily oppose the heroes or the villains. The characters were classified (again manually – see this file) into Good/Bad, but there are some difficult cases: a small number that don’t have a known allegiance and a slightly larger group whose allegiance is, let us say, flexible. Either they oscillate (e.g. Loki) or follow a redemption path (e.g. the Scarlet Witch) – we lump these cases into “It’s Complicated”.

Nearly three quarters of mook conflicts involve a named protagonist. That highlights their roles in (i) showing the heroes superpower, and (ii) increasing the level of action.

Much more rarely a mook opposes a “complicated” hero and even more rarely a villain. The MCU doesn’t seem to use mooks as wholesale fodder for villains to wipe out (Ragnarok is an exception) so much as obstacles for the heroes before they get to the big bads. And even the major group of “good” mooks turns out to be evil (spoiler: SHIELD is really Hydra).

Conclusion

Without his Storm Troopers (or his Clones) the Emperor of the Star Wars universe would have been nothing more then a personal menace with a great need for a plastic surgeon and a better fashion consultant. And where would Sauron have been without his Orcs. The power of most Masterminds lies with their minions—the faceless hordes who exist to do (literally) only the Mastermind’s bidding and work their evil upon the game world.

Mooks make the world go round. Not literally. There isn’t a secret cabal of millions of mooks running in giant equatorial circles to spin up the globe. (But wouldn’t that be cool!)

Mooks make action movies move. They provide colour and background and context and pace. In extreme cases, up to 60-70% of action in a movie involves mooks. So they can’t be discounted as an unimportant part of the movie industry. And their role and importance shouldn’t be based on whether they speak or not. At the very least it would make my life easier if they were given more formal credit (it would save me a lot of manual data entry).

In other ways the findings here aren’t surprising at all. But they highlight the nature of heroes as compared to villains in our narratives. Heroes tend to be independent and self-sufficient. They aren’t managers (or if they are – Tony Stark – they aren’t very good managers). Our idea of a hero is someone who makes their own way in the world. They achieve through their own drive, knowledge, bravery, force of character and ability.

Villains, on the other hand, we associate with bosses: people who control and dominate others. Villains use others for their evil schemes. Villains corrupt others to their purposes.

These are tropes that go way beyond the MCU, superhero movies, or movies in general. We can see them in cowboy movies, in fairy tales, in mythology, and in a large part of Western literature. Probably they appear outside the West as well, but I’m not in a position to say for sure.

For me, understanding mooks in the MCU has led to a better understanding of our (Western) values, in particular how they are expressed in the narratives that we use to build our ideas of morality. We don’t tell heroic stories (at least not often) about brave industrialists whose tireless work participating in board meetings led to the construction of temple-like factories, and whose personal ambition was tempered by their desire to do good8. Those stories are generally dark satirical comedies. We tell stories about the brave individuals who save kittens (and other innocents) from said industrialists and their evil corporations. That reflects how we think about those roles in our society. And that ties into one of the underlying themes of the blog – to understand how superhero stories reflect and affect our society.

Available Data

Just a quick note to remind you that most of the data used here is available at https://github.com/mroughan/AlephZeroHeroesData/tree/master/MarvelCinematicUniverse. GitHub renders CSV files nicely so you can interact with them. The conflict data itself isn’t up there yet (it will once I convert it into a more readable format) but at the moment the input files are

- An list for de-aliasing named characters

- The alignment of characters

- The categorisation of the mooks

and the output files are mooks’

They’re all CSV (though sometimes with ‘shell’-style comments). Hopefully the formats are self-explanatory (though more on that later). Please use as you need. Corrections can be put forward as “issues” on GitHub.

Footnotes

- The Hydra agents are posing as SHIELD agents. ↩

- We might technically know the actors, but their characters in the movie have names like: SHIELD Agent, or Strike SGT #1. ↩

- Movie genre classification isn't a perfect science. Superhero movies could be seen as being in the overlap between Action and Sci-Fi or Fantasy movies. For our purposes the structural elements of the movie are more important than the content, so classifying the movies as "action" is more useful. ↩

- Silent roles might not be completely silent. In the British film industry an extra can speak 12 words (presumably the British expect even extras to engage in day-to-day politeness). ↩

- For the purposes of this article a "named" character will be one who has a proper noun designation, e.g., Tony Stark. Characters are not considered named if they are described by their relationships or role, e.g., Tony Stark's secretary, or SHIELD agent. ↩

- The award for "The Worst Alternative Choice of Meaning" goes to 'significance' as defined by statisticians. The technical meaning is just slightly close enough to the common meaning to cause endless confusion. ↩

- I group mooks into their most obvious organisation, though the process isn't completely straight forward. Some movie credits list organisations for mooks, but it isn't always easy to attach the right group. Other times the grouping in the credit is (deliberately) misleading. How many SHIELD agents are really Hydra agents? ↩

- Willy Wonker is the exception! ↩