A mathematician, a physicist, and an engineer walk into a bar. The bartender says, “Hello, Professor Gauss.”

Who was the first data scientist? There is a nice answer on Quora. It starts with Aristotle and goes from there.

Aristotle is listed at the top of Quora’s answer because he is credited with founding Empiricism. He asserted that we should learn from observations, not pure thought. It doesn’t sound radical today, and I sometimes wonder if it was really radical in his day. Empiricism was pretty different from existing philosophies but not so far from the way most of us think: “You have to see it to believe it.”

Regardless, Empiricism is the keystone of modern science, and many others have contributed to this over the course of several thousand years. So let’s start by noting that when I say “Who was the first data scientist?” I am not talking about the first scientist, to which Aristotle has a strong claim.

I don’t mean the first statistician either. There are many who contributed to our understanding of statistics and probability over the years. They date at least to the Arab philosopher Al-Kindi in the 9th century with An Account of Early Statistical Inference in Arab Cryptology. An early fave of mine is Blaise Pascal (1623-1662), whose contributions include improving our understanding of fluids, the invention of the mechanical calculator – the Pascaline – (long before Babbage) and the underlying principles of gambling, which is the starting point of research into probability. But statistics is not data science. Many statisticians are also data scientists, but data science is bigger than just statistics.

David Donoho pointed out in 50 Years of Data Science (2017) that there is a long argument about the relationship between data science and statistics, but that most proponents of the newer field see statistics only as part of a larger context. For instance, Donoho dates data science back to Tukey with “The Future of Data Analysis” (1962). Tukey was a strong statistician and re-inventor of one of the most beautiful algorithms of all time, the Fast Fourier Transform. He was also the person who coined the term “bit”. He said

For a long time I have thought I was a statistician, interested in inferences from the particular to the general. But as I have watched mathematical statistics evolve, I have had cause to wonder and to doubt. …All in all I have come to feel that my central interest is in data analysis, which I take to include, among other things: procedures for analyzing data, techniques for interpreting the results of such procedures, ways of planning the gathering of data to make its analysis easier, more precise or more accurate, and all the machinery and results of (mathematical) statistics which apply to analyzing data.

To me, Tukey’s vision was that rather than silos of knowledge such as statistics, we need a synthetic discipline that crosses barriers. Tukey called it data analysis. The name data science came later, coined by William Cleveland in Data Science: an Action Plan for Expanding the Technical Areas of the Field of Statistics (2001), I think because data analysis had come to mean something far more specific than Tukey’s vision. Cleveland explained said what comprised his vision:

- Multidisciplinary investigations (25%)

- Models and Methods for Data (20%)

- Computing with Data (15%)

- Pedagogy (15%)

- Tool Evaluation (5%)

- Theory (20%)

He and Tukey and many others were trying to change an agenda, and reduce the proportion of time spent on statistics theory in comparison to the other tasks. But as a working definition it isn’t easy to apply, so we need to look further.

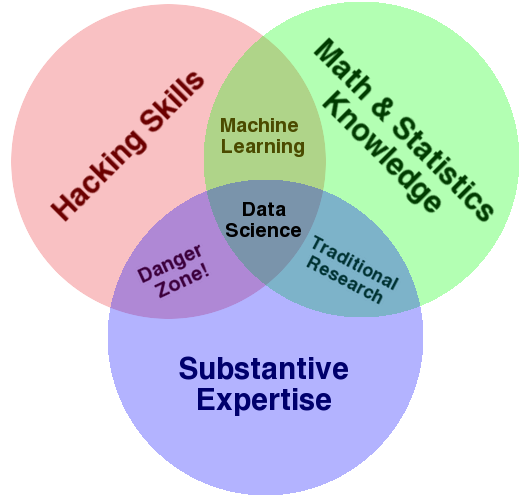

Instead I like Drew Conway’s Venn Diagram: it shows data science as the integration of three main areas. None of these is data science by itself. Few people sit in the intersection. Most contribute to data science through maybe two pieces. That is OK! The point is not to be the all-singing, all-dancing trio. But when that happens it is cool.

And that is why I say Gauss should be considered the first data scientist; because he did it all.

Johann Carl Friedrich Gauss (1777-1855) was a child prodigy, correcting his father’s math when he was only 3. And there are other stories.

He was primarily a mathematician. He made major contributions to analysis, number theory and geometry. Just to give you an idea of how big these were, he had made multiple discoveries by the age of 21 that would each have made another man’s career by themselves. When Alexander von Humbolt asked Laplace who was the greatest mathematician in Germany, Laplace answered “Pfaff.” Confused, Humbolt asked “But what about Gauss?” Laplace answered “Oh Gauss. He is the greatest mathematician in the world.”

However, he had a second life: he was also an astronomer and physicist. His work on magnetism is recognised in the unit for flux being named after him and in Gauss’s law. He was, with Newton and others, of the breed where there was little distinction between physics and mathematics. However his work on astronomy is what interests me here.

Gauss discovered how to extrapolate the position of an astronomical object from very limited observations. Newton described this as the hardest sort of problem. Gauss’s prediction of the position of Ceres was (perhaps) the first case of (model-based) statistical prediction ever. That is data science: using data (usually noisy, and limited data) to perform a real-world task (often prediction). In the course of his work in astronomy Gauss developed1 the least-squares method for fitting a curve to data (something that is used incredibly often throughout statistics and engineering), and he needed to deal with errors in the measurements. The Gaussian distribution is named after him as a result.

Gauss also had “hacking skills” or at least the 19th Century version of those. Obviously he hadn’t an electronic computer. However, to compute the orbit of Ceres, he needed an algorithm and thus it is that he is the original discoverer of the “Cooley–Tukey” Fast Fourier Transform algorithm2. He shows us that “hacking” is not just about cool computer languages and huge computer clusters. It’s about being clever and using computing resources (even pencil and paper) efficiently. Big data is relative!

The fact that Tukey – the modern creator of the field of data science – and Gauss both independently invented the Fast Fourier Transform should tell us something fairly profound. The FFT (as it is often abbreviated) uses the idea of divide and conquer, which is at the heart of much today’s modern big data infrastructure. It does so in an elegant and mathematically sophisticated way, but the essential idea is that a calculation can be broken into parts, each of which is easier than the whole (in the case of the FFT, much easier) and then brought back together — that is a profoundly important idea in data science.

Gauss also applied his skills to surveying, one of the other early applications of statistics to large-scale data. Again he showed his integration of mathematics and statistics with domain knowledge3 and with the ability to actually do the computations.

If Gauss had a failing as a data scientist it is that he was not a great communicator. He worked on proofs until he felt they were perfect, and held back mathematical discourse as a result. And his proofs, though profoundly rigorous, are so terse as to be hard to follow for even seasoned mathematicians. On the other hand, he seems to have been a nice guy – he was devoted to his mother, and looked after her himself in her old age, and though he had only a select group of friends he seems to have had a strong relationship with them.

There have been many people since who have been profoundly important for data science. Have a look at, for instance:

- https://www.analyticsvidhya.com/blog/2015/09/ultimate-data-scientists-world-today/

- https://www.quora.com/Who-are-the-most-notable-and-influential-data-scientists

But there will never be another Gauss. He should be better known in data science circles than just a name on a distribution that also get’s called “normal.”

Gauss is sometimes called the Prince of Mathematics. I think we should add to this that he is the Duke of Data Science.

If you want to read more about a guy who was an actual superhero (he didn’t wear tights that I know of, but he certainly was a supergenius) I can heartily recomend E.T. Bell’s wonderful book Men of Mathematics.

- There is a dispute about who created least squares first: Legendre also has a claim. ↩

- The “Cooley–Tukey” Fast Fourier Transform algorithm is named after them because their reinvention in the context of digital computers is the one that spread. ↩

- Gauss even invented a surveying tool, the heliotrope. ↩