Intro

Thor: Join us. Join Earth’s mightiest heroes.

Mantis: Like Kevin Bacon?

Thor: He may be on the team. I don’t know. I haven’t been there in a while.

How many Avengers are there? It should be an easy question, but it isn’t. Even if we restrict ourselves to the Marvel Cinematic Universe (MCU), which we’ll do here, the group changes over time, and some participants aren’t official Avengers.

The best way to measure that would be to just count, but if someone was an Avenger for one day only, should they be included?

And if they aren’t an official Avenger, but almost always end up in the team, maybe they should be included?

What we need is a participation based measurement; not a hard “you’re in or you’re out” type of decision. We need a softer metric that lets you be Avenger-ish or Avenger-adjacent. So that’s what we are going to do today.

We’re going to apply it to the MCU movies, and we’re going to start by looking at something as simple as the effective size of the cast of the movies. But ultimately I want to work towards the question “How many Avengers are there?”

How do we measure a cast?

The simplest approach to measuring the number of characters in a movie is to look at the size of the cast. Credit lists should give us that, right?

Wrong! Movie credits are not a uniformly defined source of data: the onscreen credits of Closer (2004) list 6 cast, whereas Stuck on You (2003) credits 383 actors. In the MCU Iron Man 3 seems to have the largest cast (at 110), but it is just a linear plot, primarily involving Iron Man. On the other hand Avengers: Infinity War includes almost every prior superhero from the franchise but has a rather moderate credited cast of 56.

There is no unique definition of how a credit list is constructed, and it has varied historically and regionally in level of detail, and the types of activity that are credited. In the United States, the standardisation of credits starts around the 70s, but has evolved continuously, and is still evolving1.

The problems are that “credit” can have implications for cost, and as credits are often posted before the movie, some can reveal spoilers. So there are incentives to play with the list. Also, cameos and some extra parts are often uncredited.

You might think that if we looked at “named” characters (characters important enough to require a proper noun designation) the issue would be resolved, but it isn’t. By this measure Thor: Ragnarok has almost the smallest cast (18), but it is a big movie involving multiple settings and many characters.

Even more complex is the consideration of a character’s contribution to a movie. Should a character who says one line be counted the same as the title character?

Our goal is to find an effective metric for the “population size” of the cast of a movie. Luckily the problem has been considered extensively in the context of measuring ecological diversity of a habitat, and there are several parallels. In ecology there is a need to understand not just how many members of each species are present in a habitat, but to capture what this means in terms of diversity.

One measure used in ecology is based on Shannon entropy. There are lots of good reasons to use this approach. I’ll give a quick definition and some intuition below.

Shannon entropy

The entropy of a distribution describes its inherent uncertainty, and a higher uncertainty suggests greater diversity. Simply put, if it is harder to guess what species you are observing (assuming you know nothing about taxonomy) at any given moment, there must be more possibilities out there. An analogy is a multiple choice question – if it is harder to guess the answer, then there is more entropy. Think of it as measuring how many effective answers there are to the question. Some answers may be obviously wrong, so you don’t count them seriously.

Shannon entropy2 is defined by \[ H({\mathbf p}) = - \sum_i p_i \log_2 p_i \] for a probability distribution \({\mathbf p}=\{p_i\}\) .

This isn’t enough for us – its unit are “bits” not characters. However, if we take \[ \hat{N}({\mathbf p}) = 2^{H({\mathbf p})} \] then we can assign this units of “characters”. It’s a measure that is sometimes called perplexity in the context of information theory because it can be seen as a measurement of how hard a random event is to predict. A higher perplexity means it is harder to guess what will happen.

So, think of our measure of cast size in the following way. Imagine you blind-folded yourself, and put noise-cancelling headphones on, and then tried to guess which character was performing at some given time in a movie you have never seen before. Your chance of guessing correctly depends on the effective cast size.

If the cast is large, you are unlikely to guess correctly. If the cast is small, you have a better chance. And it naturally takes into account of characters who appear only briefly – they change the metric only a little because there is little chance you would guess them.

Shannon entropy of what?

Shannon entropy is calculated for a probability distribution \({\mathbf p}=\{p_i\}\) . The question that immediately arises is “what distribution?” There are several possibilities. Without wanting to divert the story too far, we tried a couple, and they give complementary views of the data. The one I will describe here is based on the proportional contributions of each character to the action of the movie.

Conflict data

Here is a taste of the data. The table below lists the characters in the original Iron Man along with their frequency of participation in the action. The raw data is here. Amongst other details it lists individual conflicts and who was involved for most of the MCU movies. There’s a lot in the file, so I will refine it down simply to counts of each characters’ contribution as shown in the following table for the movie Iron Man.

A few notes:

The data concerns the contribution of the characters to the action of the movie, so for instance Yinsen only gets a small part. If we used a dialogue-based metric it would be different, but complementary.

Character aliases have been resolved, and single canonical names used for each. See this blog for more details. For instance, Rhodey isn’t called War Machine yet, but he will be, and we want to use common names across the whole MCU.

There are several characters listed as mooks. These are unnamed characters who, never-the-less, are important for the action in the movie. See this post for more information about these.

The resulting metric for Iron Man is \(\hat{N}(Iron Man) \simeq 4.7\) characters.

That is is considerably less than the number of characters in the movie, but isn’t such a bad representation of the important characters. There are only really three important characters (Tony Stark/Iron Man, Obidiah Stane/Iron Monger and Pepper Potts) plus a short list of other named characters, and then various mooks that in total add up to about 1.7 other characters.

How many Avengers?

Loki: What have I to fear?

Tony Stark: The Avengers. It’s what we call ourselves. Sorta like a team. Earth’s Mightiest Heroes type thing.

Loki: Yes. I’ve met them

Tony Stark: Yeah, takes us a while to get any traction I’ll give you that one. But let’s do a head count here. Your brother, the demigod. A super soldier, living legend who kinda lives up to the legend. A man with breathtaking anger management issues. A couple of master assassins and YOU, big fella, you’ve managed to piss off every single one of them.

Loki: That was the plan.

Tony Stark: Not a great plan.

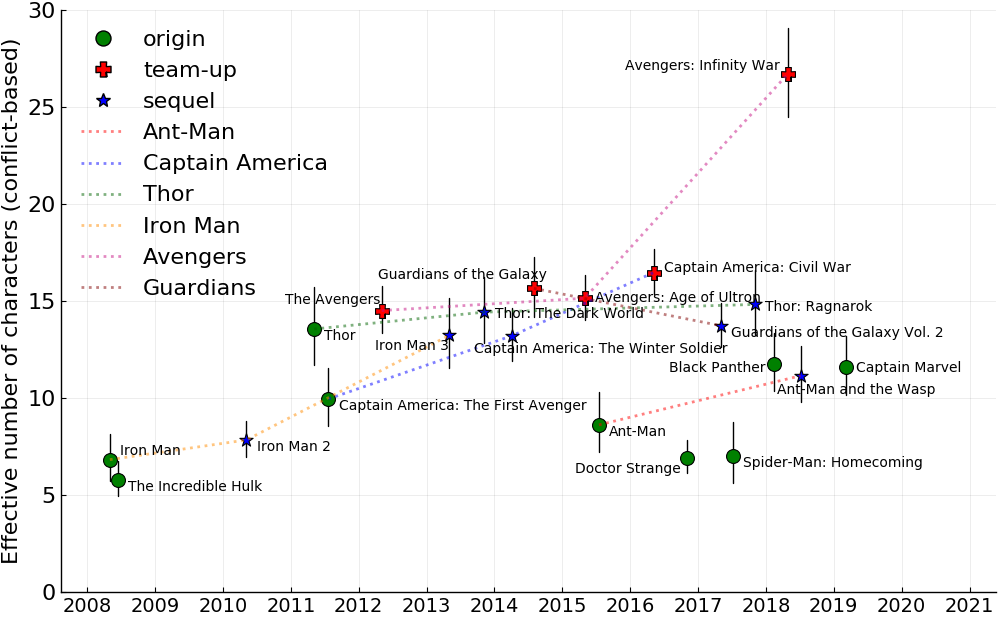

The results get interesting when we look across the movies. At the moment, End Game and the latest Spider Man aren’t included (they weren’t available when we started the analysis), but all of the other 22 movies are in.

We see some interesting patterns, most obviously there is a general inflation in cast sizes in most sequels (the exception is the Guardians of the Galaxy movies). Subsequent movies tend to have larger casts of characters. That shouldn’t surprise anyone.

To understand the patterns better, we should look a little bit at a way of categorising movies.

Types of movies

In order to better understand results, the movies are classified into types within the MCU, based on the their characteristics and relationship to other movies in the franchise. We classify movies as:

- origin movies – these have the first major appearance of a character, and often explain some of that character’s back story;

- sequels – these are movies that follow on directly from another with a large overlap in cast and plot elements; and

- team-ups – these movies involve a group of superheroes forming into a team for a larger purpose.

The classification is soft in the sense that many of the movies have aspects of more than one type of movie: for instance, most movies in the MCU are sequels in some sense. Other movies such as Guardians of the Galaxy is both a team-up and an origin movie for the characters in the team. Here we need to identify the primary role of the movie.

The interesting thing in terms of our results is that origin movies tend to have small casts, which grow in sequels, and then are composed into larger casts for the large team-up movies.

Who’s on first

We can use this metric in lots of ways. Another way to cut it is to look at the contributions of each character to the overall metric for the movies (the total estimate of the cast size for the MCU is 119.6, which is amazingly high – compare it to what we might expect to get for the Bond franchise).

The top five characters, in order are

- Iron Man / Tony Stark;

- Captain America / Steve Rogers;

- Thor Odinson;

- The Hulk / Bruce Banner; and

- Black Widow / Natasha Romanoff.

No-one should be surprised by this list. They are the original set of Avengers, and they each appear in a large subset of the movies. In most cases they have their own movies, the only exception being Black Widow, but she is integral to the plots of several of the other movies, and she is used to weave plot lines together. And there is a Black Widow movie planned for later this year.

Does entropy matter?

I win my awards at the box office.

The results above won’t be all that surprising to anyone familiar with the genre. It might be a surprise that we can measure cast size at all accurately given the noisy input data. However, an obvious question is “can we do anything more useful with the number?”

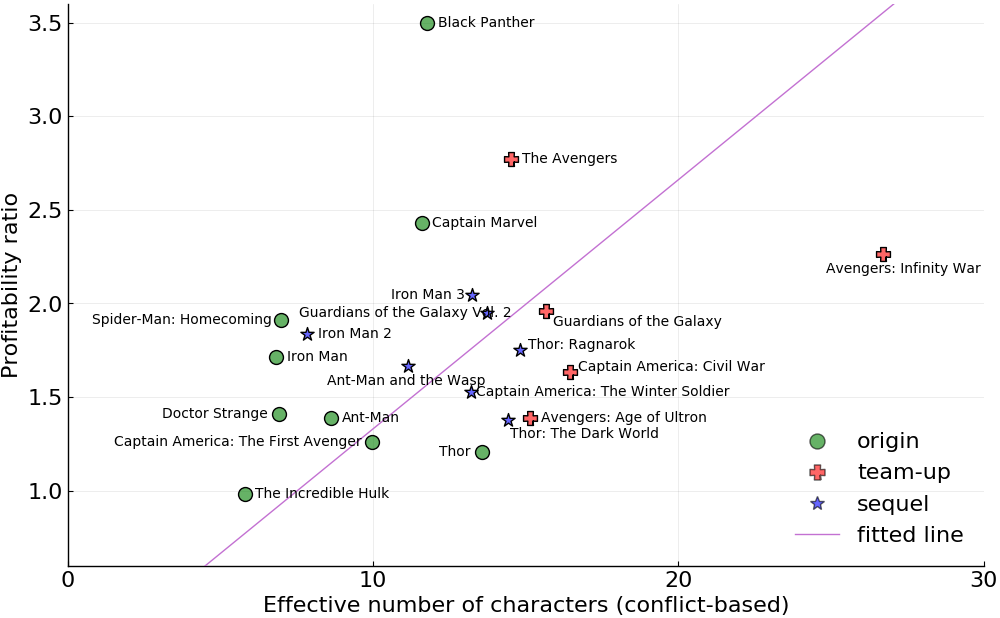

The answer is yes! The following plot shows the relationship between the cast size and profitability of the movies (the ratio of US Box Office3 to movie Budget4. There is a clear correlation.

The biggest surprise is that the effective cast size is correlated with the profitability of the movies. A bigger roll-call is related to bigger profits.

You have to be very careful about such results. What we observe is only a correlation – we can’t get causation from that. We think the true reason for the correlation isn’t just that audiences like bigger casts. The real reason is part of the uniqueness of the MCU. The producers were willing to build a series of movies towards a “team up”. They started with a sequence of Iron Man, Captain America and Thor movies that led to the tremendously popular Avengers. And then they did it again with brilliant “origin” movies for new characters, leading to bigger and bigger team ups.

That took a special kind of vision, to be willing to develop these characters over multiple movies to build up to an amazing culmination over a period of years. It’s so different from the typical franchise, which is a series of sequels (and sometimes prequels) with roughly the same set of characters.

Conclusion

Ultimately, I haven’t told you how many avengers there are. That was a cheat. The cast of characters in a movie includes villains and non-heros as well. But the size of that cast seems to be important.

What makes a movie or a franchise work is tremendously complex, and you cannot undervalue the contributions of the brilliant directors, actors and other artists who created these movies. We shouldn’t oversell the results here. They are a tiny piece of the picture, but stories are so important to humans. It is fair to say, I think, that stories are what make us human; what differentiates us from the rest of the natural world. We would really like to make a contribution to understanding what makes up the stories that are successful.

This blog entry is based on a paper that just appeared on in the PLOS ONE Science of Stories collection. You’ll find all the gory details here if you want more information. There were also articles on TechXplore and MIT Technology Review and Comicbook.com so you may have seen some of this before. We thought it worth doing our own piece about it if only to keep the blog entries churning out :)

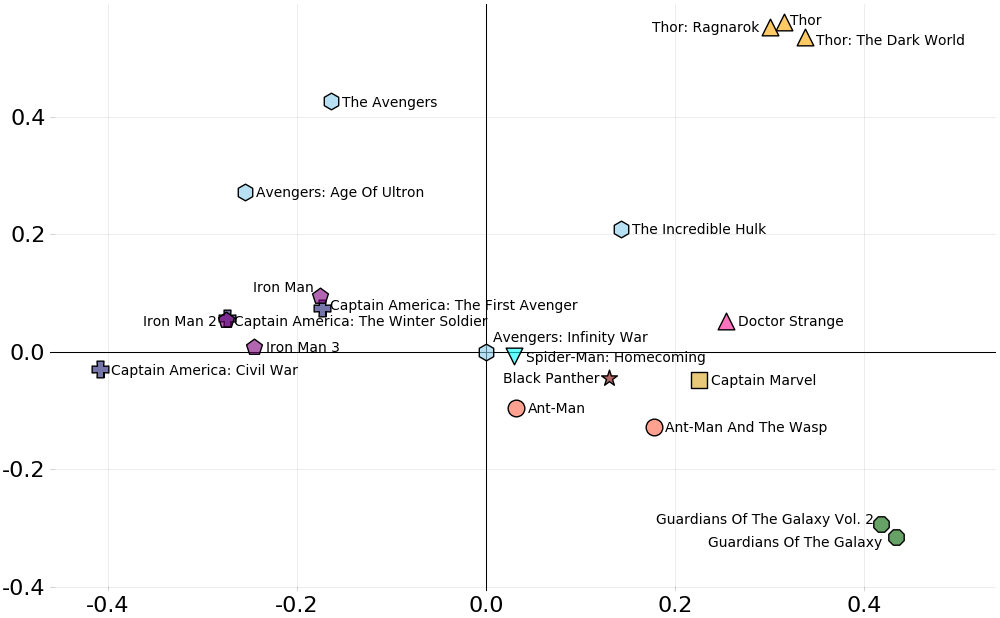

We take these results a fair bit further in that paper as well. We look at relationships between the characters in each movie, and cluster the movies according to how close their casts are.

The final picture here shows a projection of them into a 2D Cartesian space. Clusters are indicated by colour, and we can see that they match the natural clustering of the movie.

Acknowledgements

Thanks to Sylvia for editing this one.

Resources

Lots of data went into this one. The bits that we contributed are on the GitHub under a Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike 3.0 Unported License.

Source resources include:

- The Numbers for information about Box office sales etc.

- IMDbPY a Python package for retrieving and managing the data of the IMDb movie database about movies and people.

Scripts were from

- Transcripts Wiki on fandom.com

- Script Slug

The full paper is here as part of the PLOS ONE Science of Stories collection.

Footnotes

- For example, since Toy Story (1995), lists of “Production Babies” born to crew members have been increasingly included in movie credits. ↩

- I keep calling it Shannon entropy because there are different ideas of entropy: for instance Rényi entropy. Shannon’s wasn’t first, but IMHO its best. ↩

- There are many other facets to the success of a movie: DVD sales, for instance, and Star Wars is legendarily famous for its merchandising, but Box Office receipts is (i) a somewhat easier number to obtain, and (ii) is possible to obtain more quickly than other metrics, which is important in order to compare recent movies. ↩

- Exact costs are notoriously hard to obtain – here we use the budget as stated in the Numbers. ↩